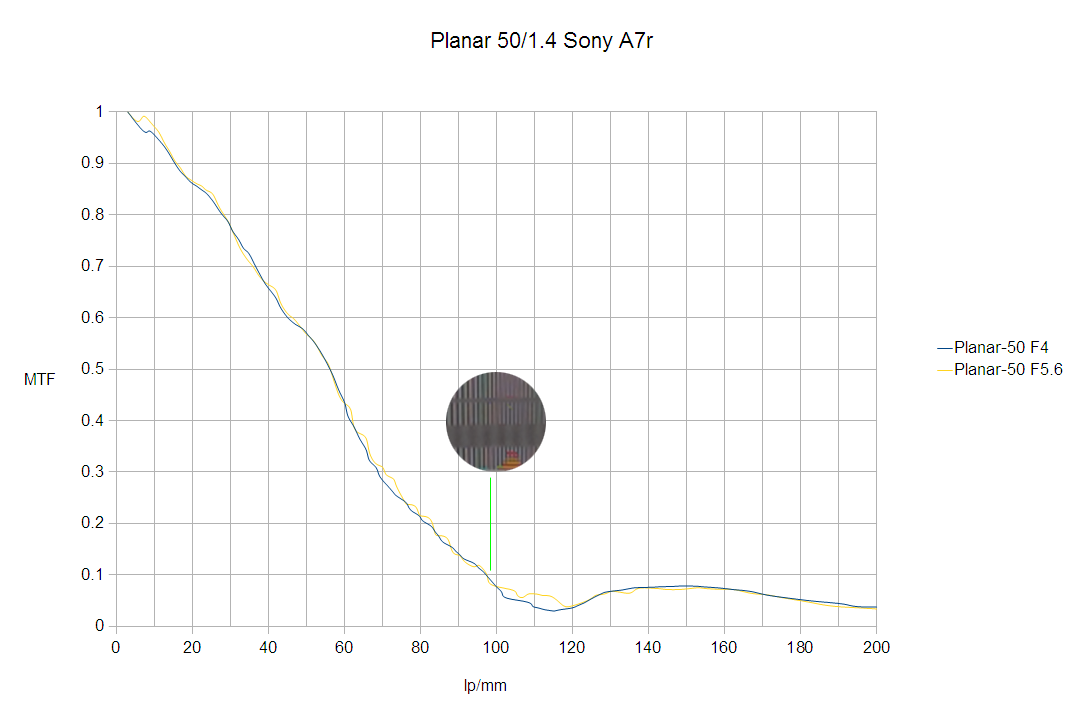

| Sony A7r, CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF |

|---|

|

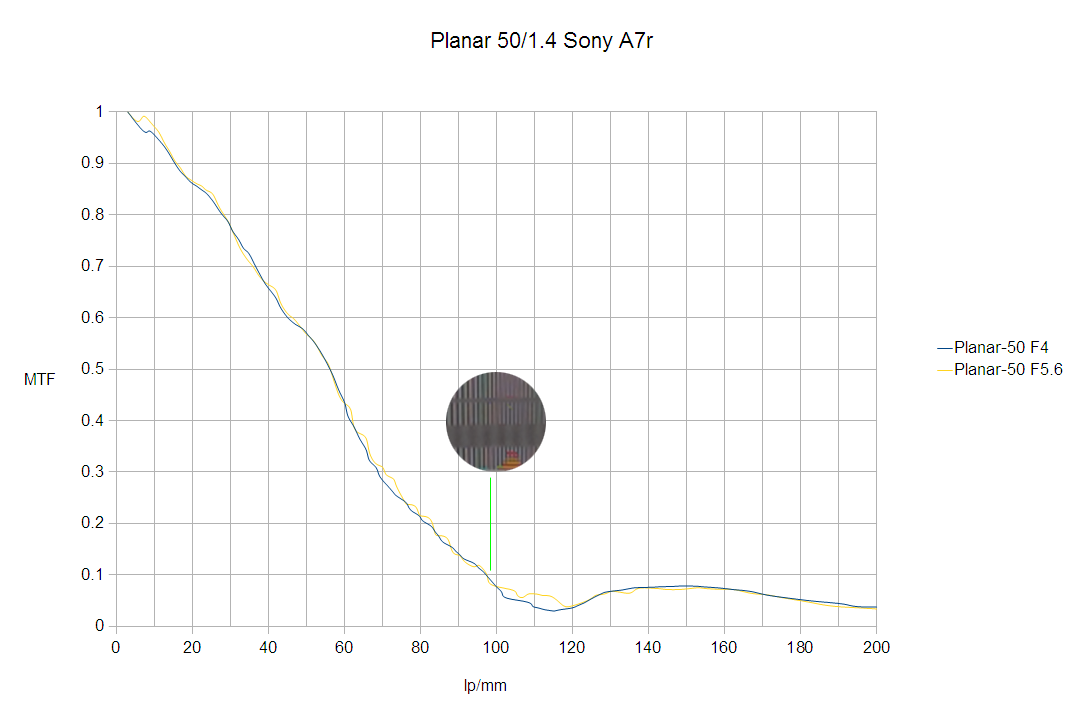

| Sony A7r, CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF |

|---|

|

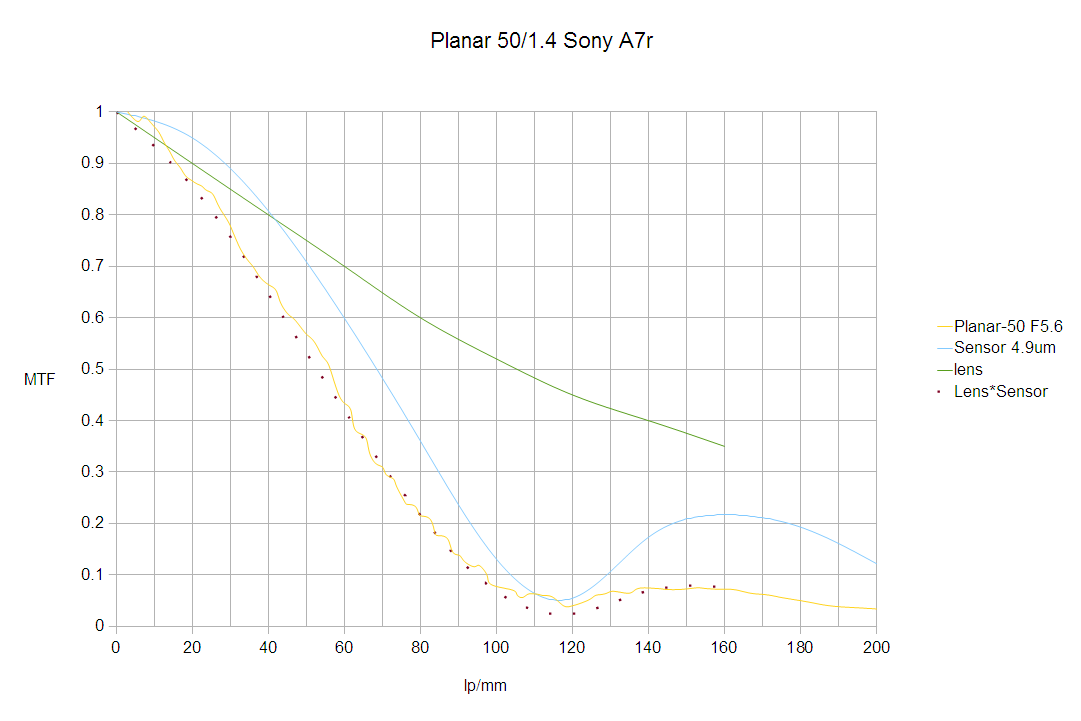

| Sony A7r, CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF |

|---|

|

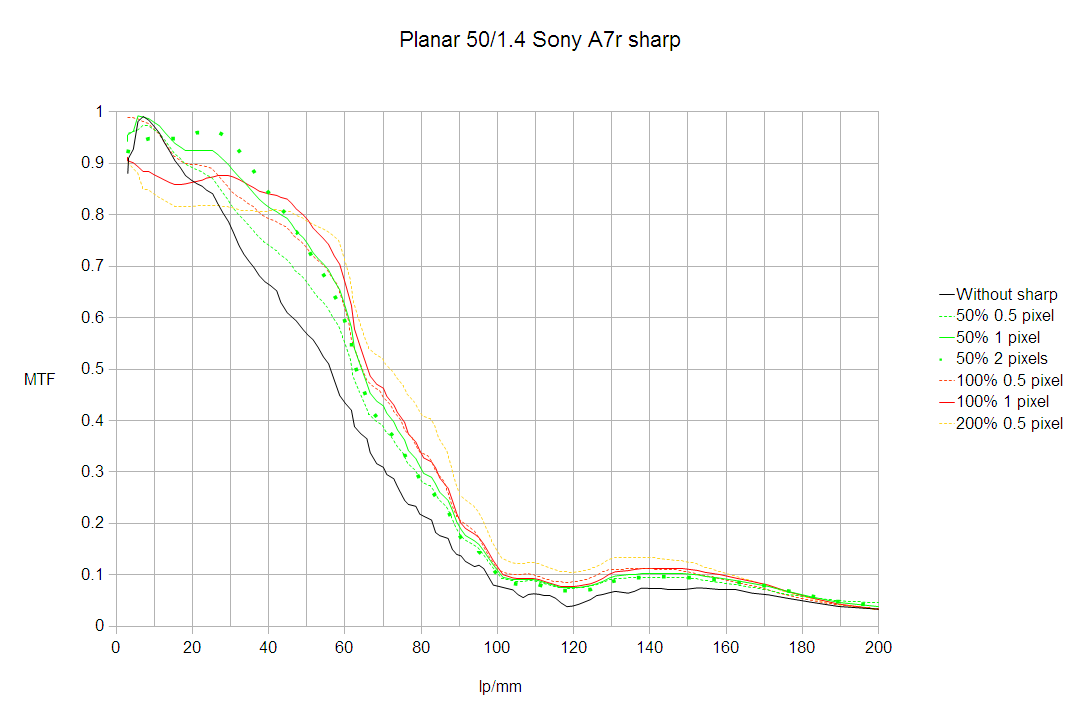

| Sony A7r, CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF, USM |

|---|

|

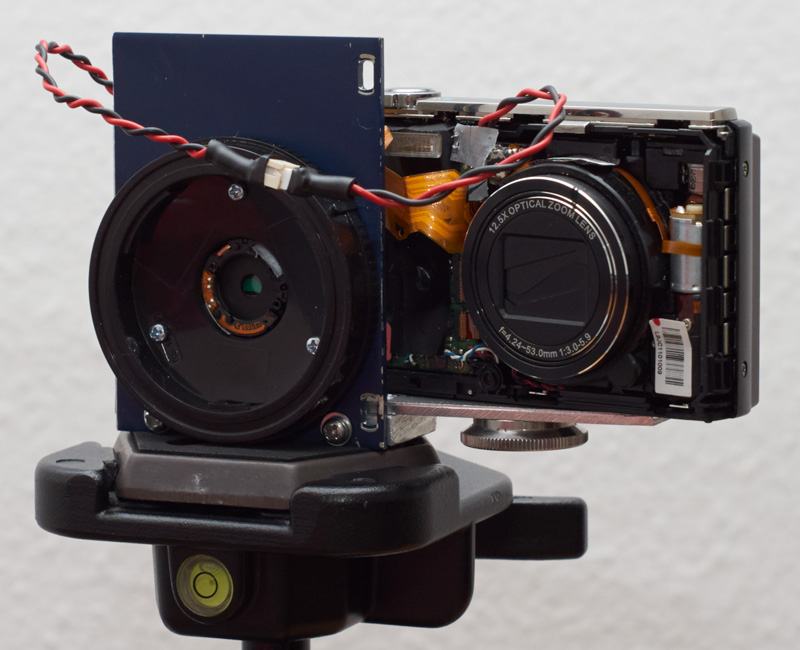

| BenQ_GH20X |

|---|

|

| BenQ_GH20X |

|---|

|

|

|

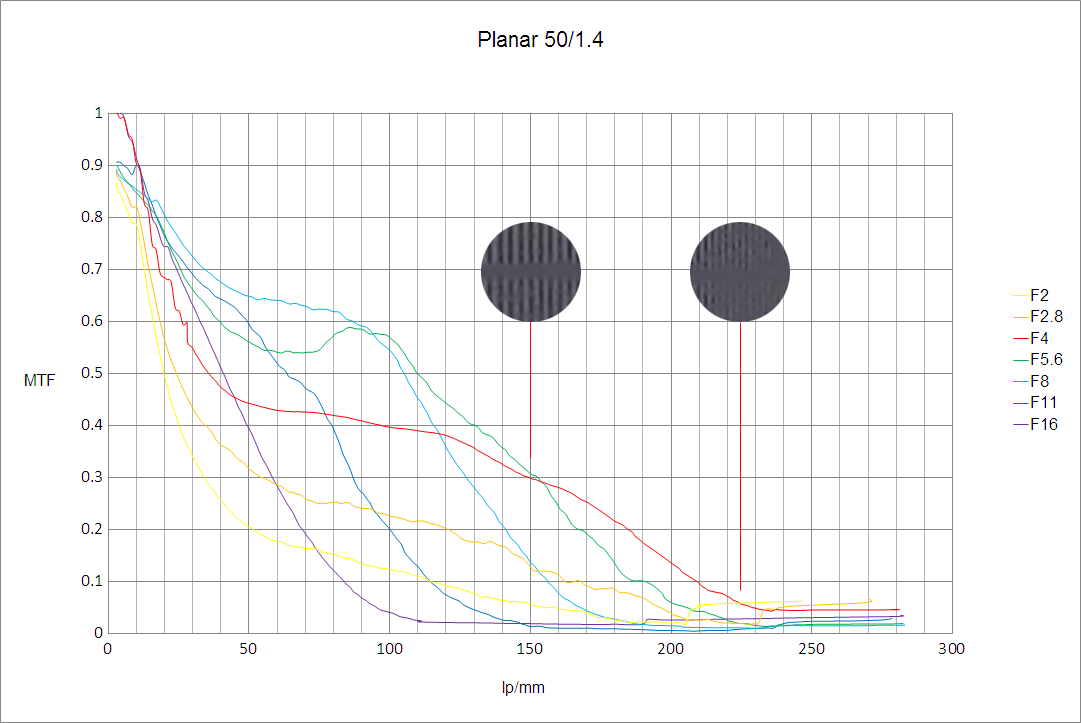

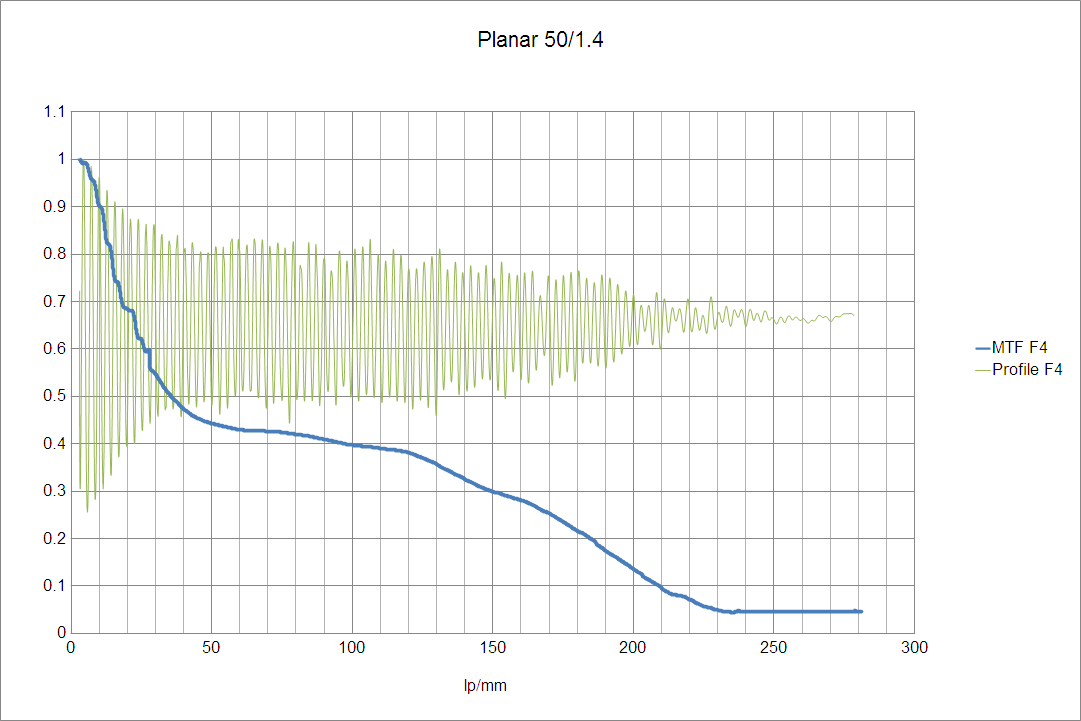

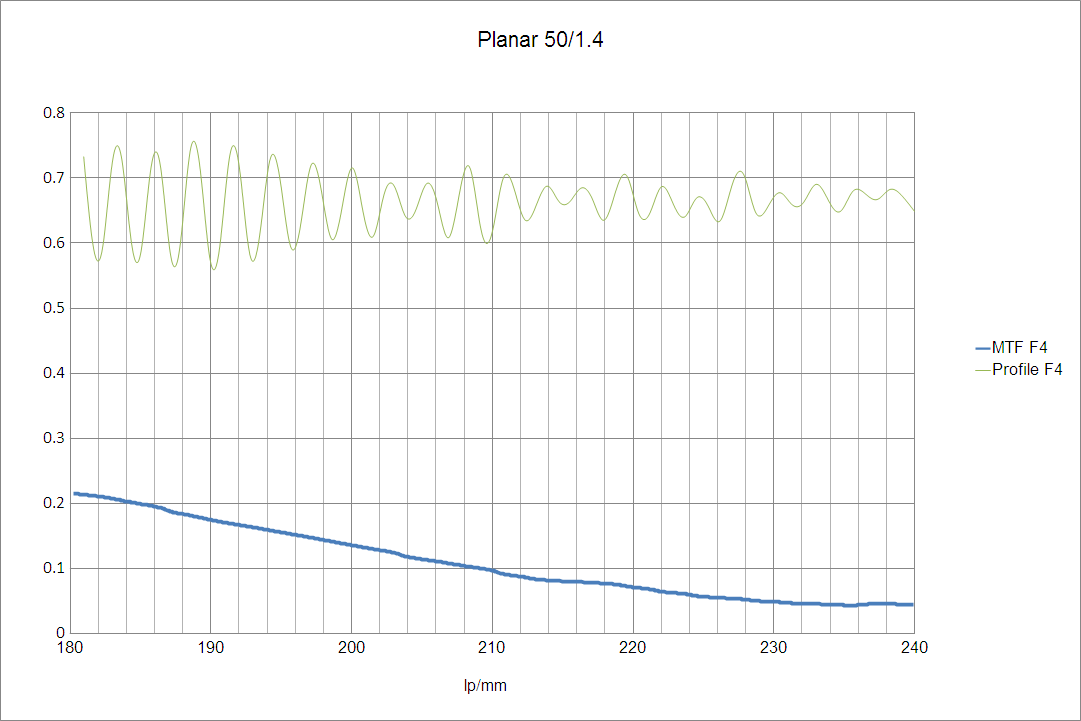

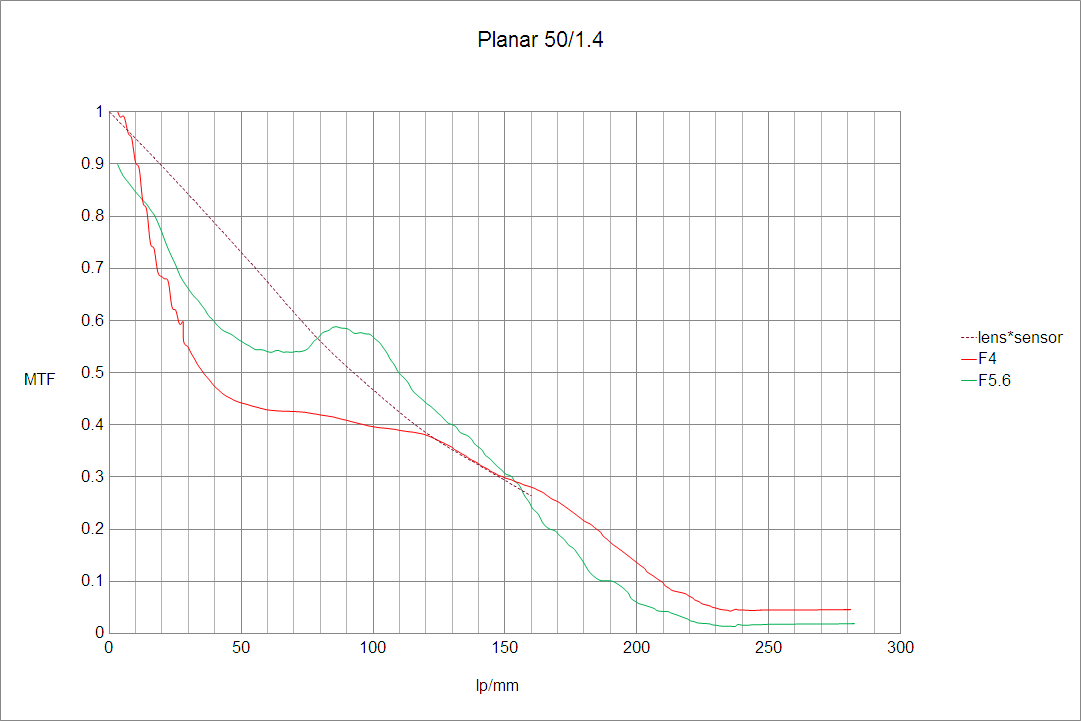

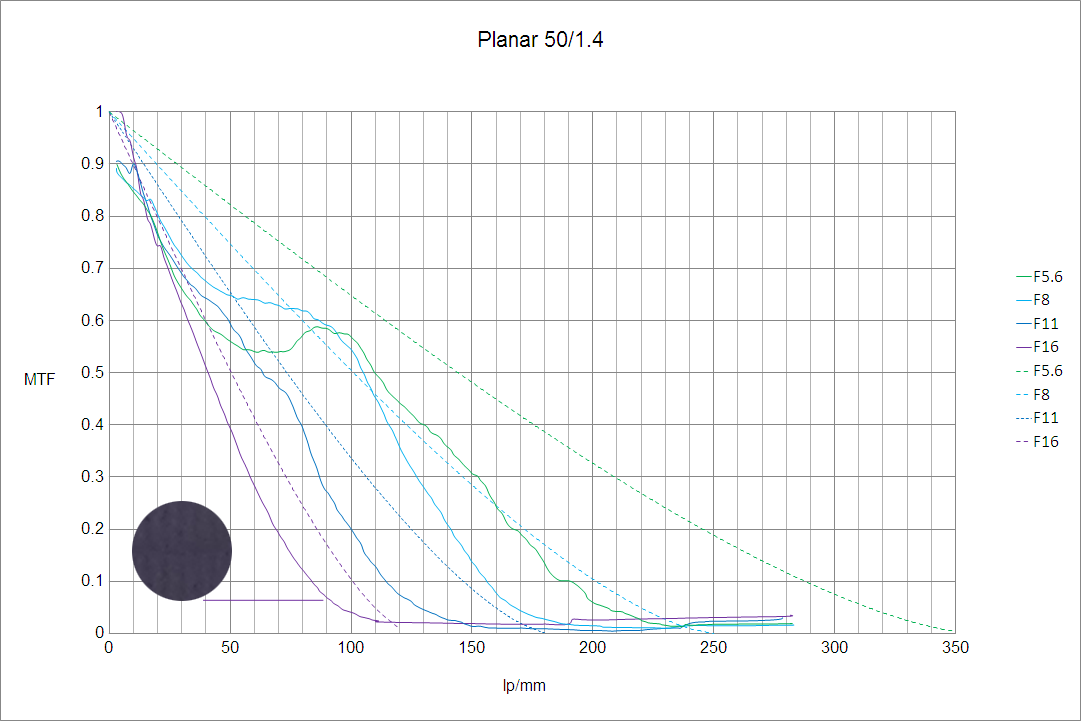

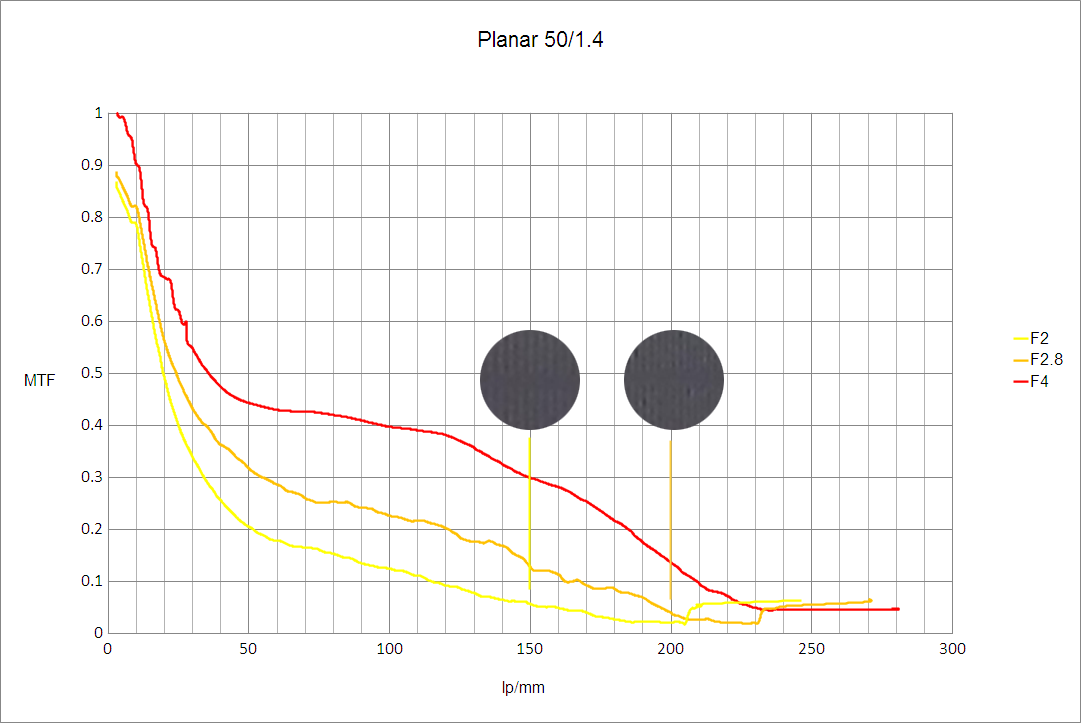

| CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF |

|---|

|

|

|

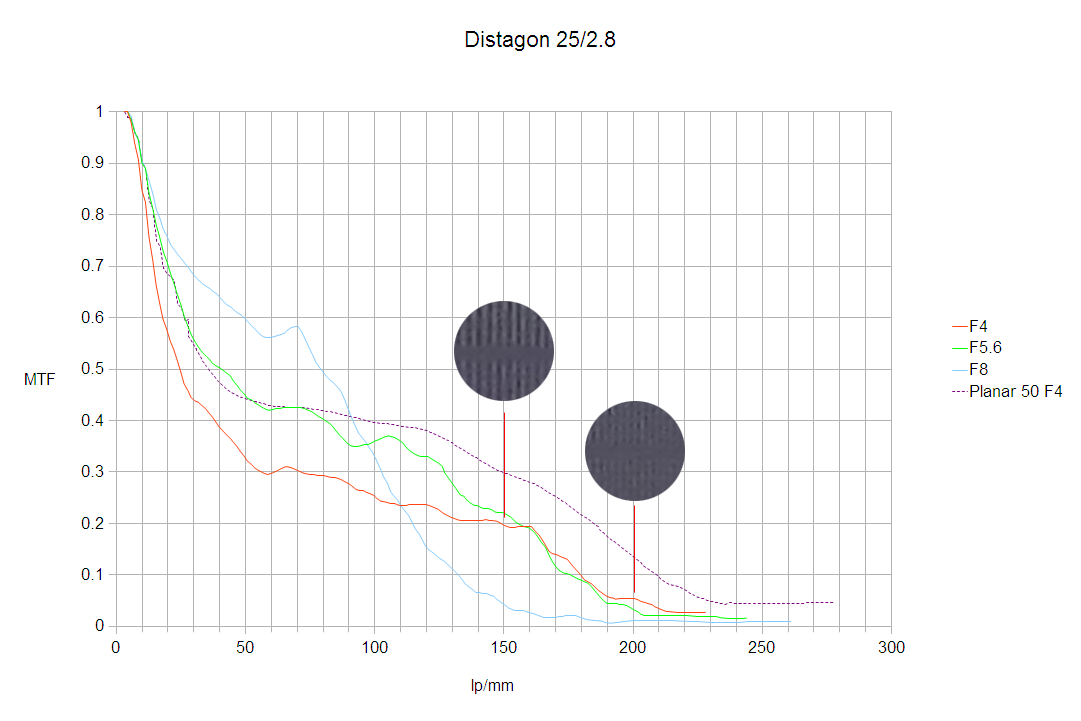

| CZ Distagon 25/2.8 ZF |

|---|

|

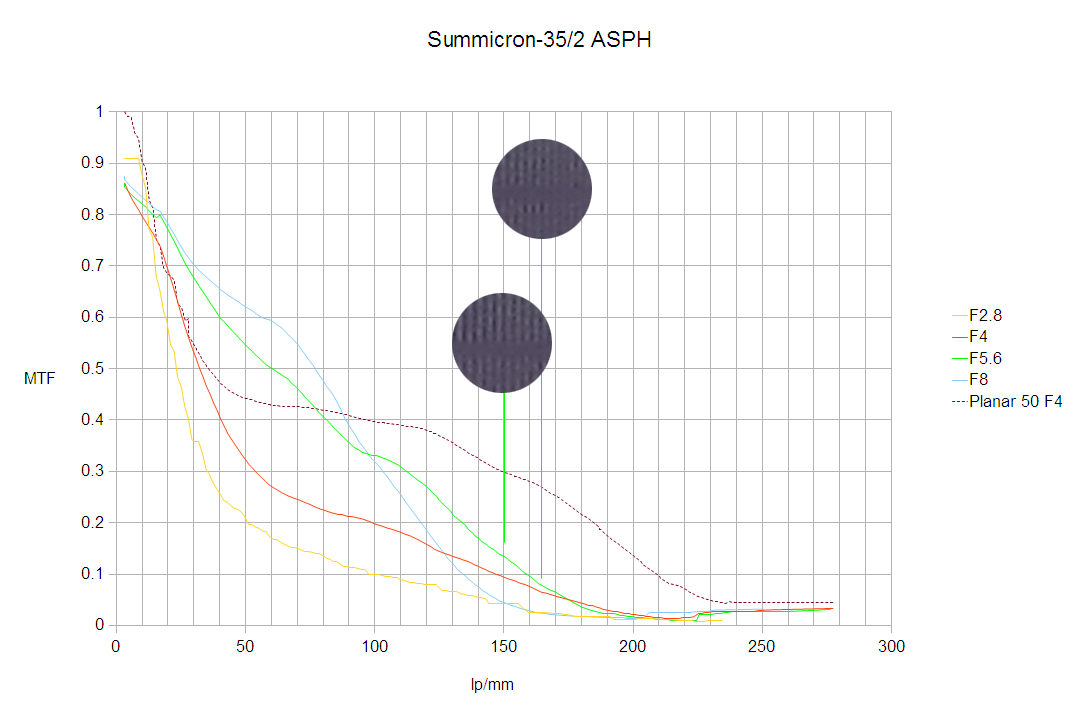

| Leica Summicron-M 35/2 |

|---|

|

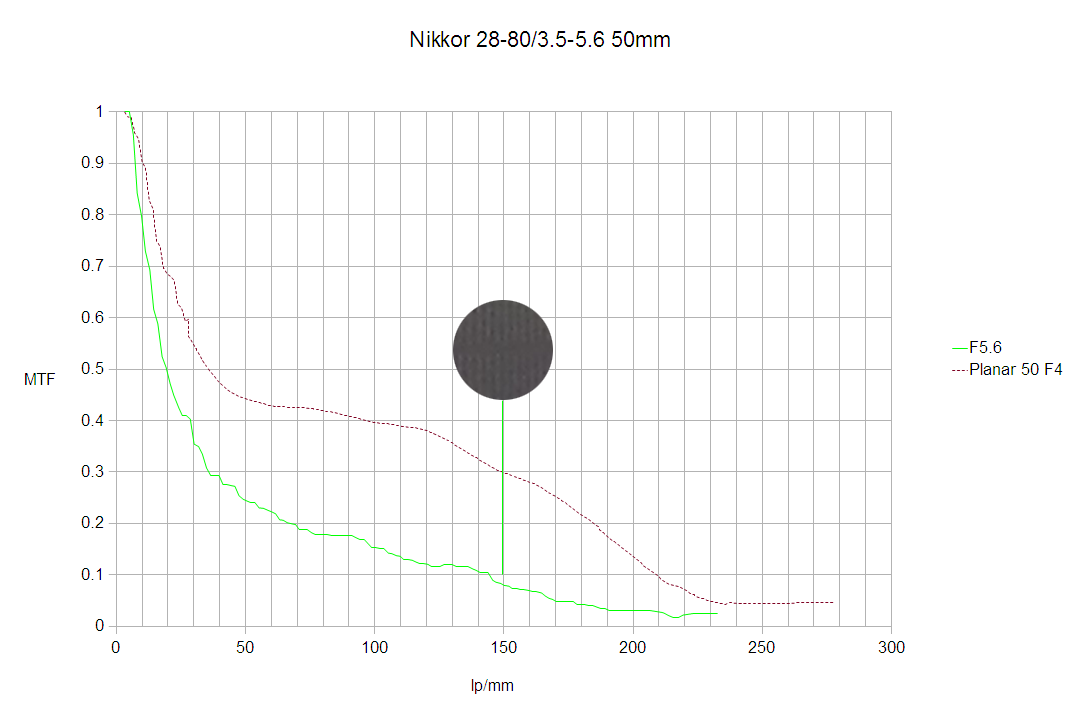

| Nikkor 28-80/3.5-5.6 with zoom positioned at 50mm |

|---|

|

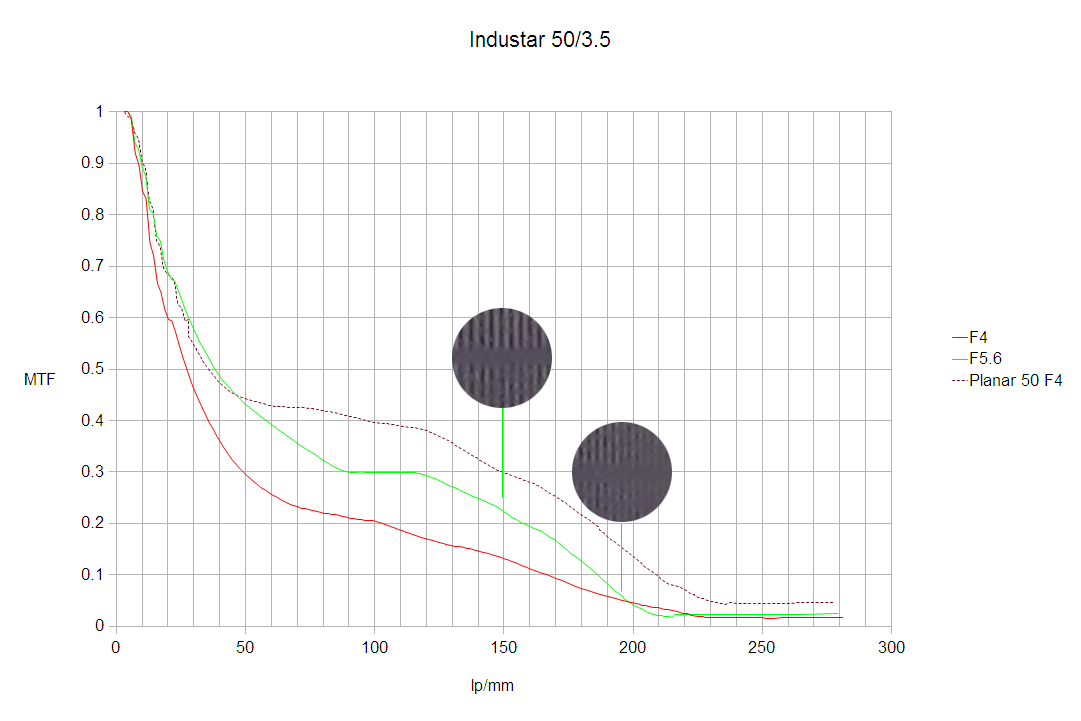

| Industar 50/3.5 |

|---|

|

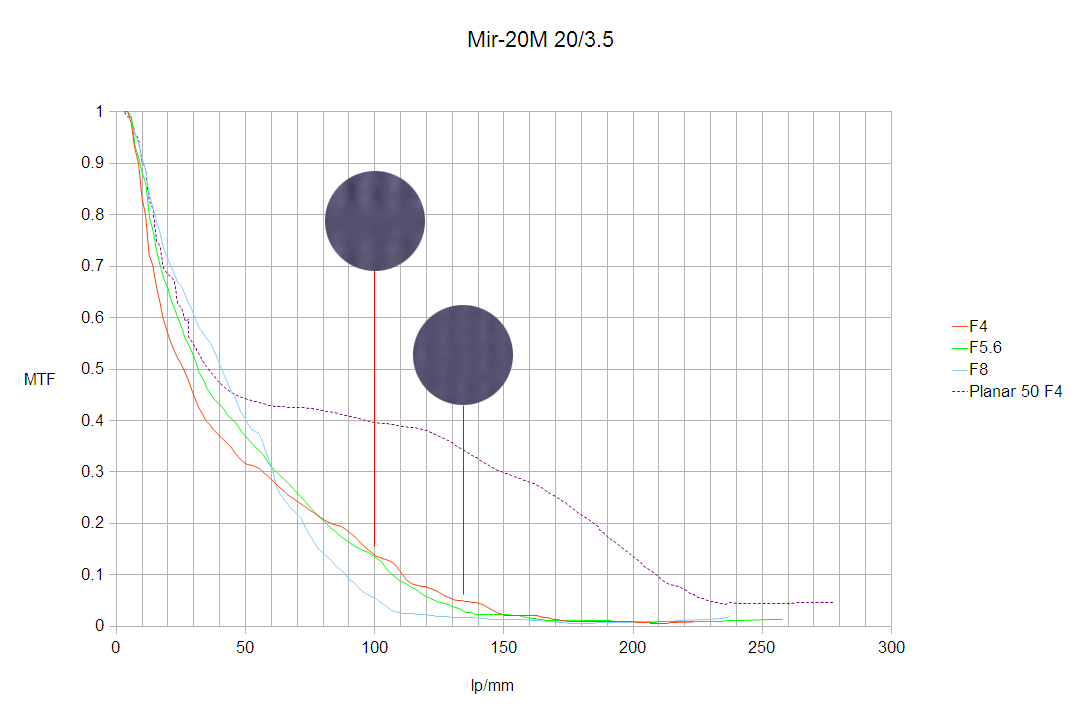

| Mir-20M 20/3.5 |

|---|

|

|

| CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF, the dotted lines represent diffraction limits for various apertures for the 500 nm wavelength |

|---|

|

| CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF |

|---|

|

| Sony A7r, 200% magnification | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF, F5.6 | CZ Distagon 25/2.8 ZF, F5.6 | Leica Summicron-M 35/2, F5.6 | Nikkor 28-80/3.5-5.6, ~50mm, F5.6 | Nikkor 18-70/3.5-4.5 AF-S DX, ~50mm, F5.6 | Industar-50 50/3.5, F5.6 | Mir-20M 20/3.5, F5.6 | Uniter-9 85/2, F5.6 | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Sony A7r with open apertures, 200% magnification | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF, F2.8 | CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF, F2 | CZ Planar 50/1.4 ZF, F1.4 | Leica Summicron-M 35/2, F2 | ||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Sony A7r, 340%. Hover your cursor over the image to see BenQ_GH20X at 100% |

|---|

|